The follow-up to Under the Big Black Sun avoids the sophomore slump by digging deeper into the history of L.A. punk

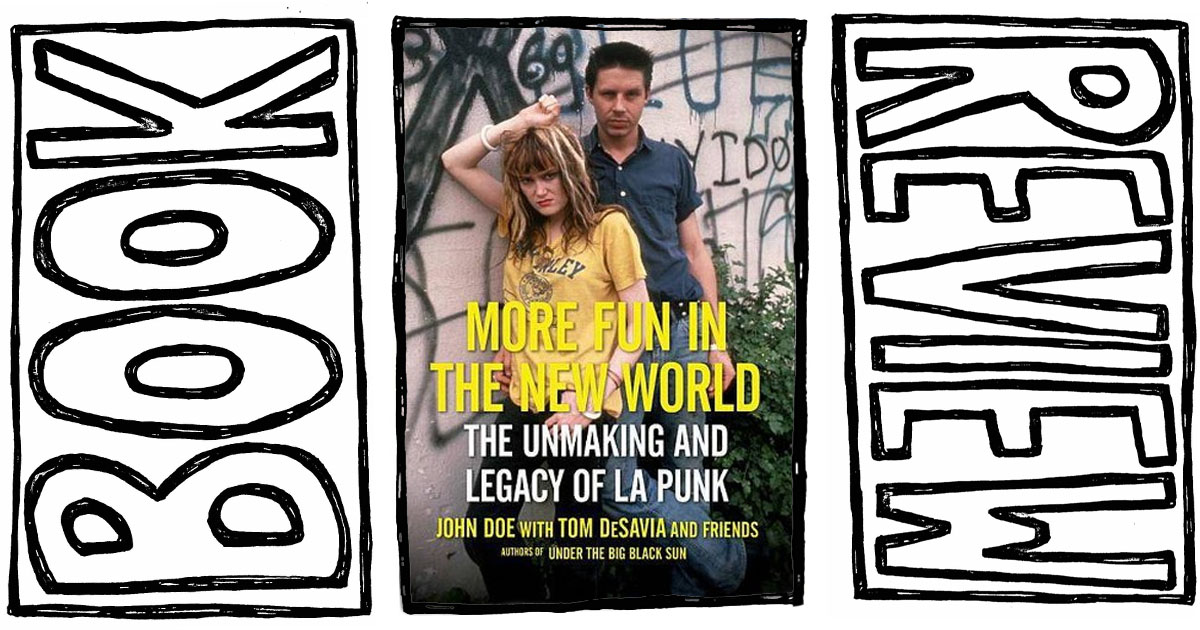

- More Fun in the New World: The Unmaking and Legacy of LA Punk, John Doe & Tom Desavia

- June 4 2019, Penguin Random House

One of the most surprising things about More Fun in the New World: The Unmaking and Legacy of L.A. Punk is its inclusion of such diverse narrators as Louie Pérez, of the Chicano rock band Los Lobos. However, as the drummer writes in one chapter of the book, “Los Lobos were not the first band to cross the L.A. River to mix it up with the punk rockers and swift-haired New Wavers.”

An oral history comprised of recollections from a broad cast of characters, More Fun in the New World was compiled by John Doe of the band X and his collaborator Tom DeSavia, a music business veteran. It’s a haphazard chronicle of the Los Angeles punk movement during the years 1982-1987. Chronologically speaking, the mid-eighties are the logical sequel to Under the Big Black Sun, the 2016 book that covered the scene’s formative period, from 1977-1982. These six years are also the perfect window from which to watch the scene’s influence play out as it diverges into various iterations, ranging from the aggressive sub-styles now associated with the genre—like hardcore and crossover thrash—to mellower, roots-based offshoots like rockabilly and cowpunk.

Effectively a sequel, More Fun in the New World rides the coattails of Under the Big Black Sun, following the Grammy-nominated first book’s formula to a tee: lyrics and conversations are slipped in between long-winded narratives (read by the authors themselves in the audiobook version). Even the title is based on another X album, this time from 1983. Narrators such as Social D’s Mike Ness and members of Fishbone add a little fresh blood to a cast of returning contributors that includes Black Flag’s Henry Rollins, The Blasters’ Dave Alvin, Jack Grisham of TSOL, and Jane Weidlin and Charlotte Caffey of the all-women new wave group The Go-Go’s, which also had roots in the scene. X’s Doe and his bandmate (and then-partner) Exene Cervenka—often thought of as the godparents of L.A. punk—preside on the book’s cover. But More Fun in the New World is less concerned with that epoch than with what came after it.

In a nod to the second-string players and fans who helped shape the movement just as much as the A-listers, More Fun in the New World features figures who were less prominent. For example, Pleasant Gehman—writer, singer of the Screamin’ Sirens, and general scenester—narrates a chapter focused on the diaspora of punk veterans to alt-country, starting with the women who felt unsafe in the increasingly violent and misogynistic ethos of the pre-riot grrrl era.

In other chapters, we hear how the music and aesthetic of L.A. punk informed the careers of nonmusicians like pro-skater Tony Hawk and Shepard Fairey, the artist now known for his Obey Giant and Obama “Hope” designs. They both write about the connection to the skate scene—punk’s “partner in visceral rebellion,” writes Fairey. He goes on to discuss how the rough-hewn DIY vibe informed his artistic sensibilities and galvanized his desire to create at any cost. “Feeling,” Fairey says, can be “more important than virtuosity.”

It’s a sentiment that rings true throughout the book. More Fun in the New World is tangential and self-aggrandizing. It feels largely unedited and unsubstantiated. These are tales to be taken with a grain of salt—especially considering the rampant substance abuse that gripped the L.A. music community and inevitably influenced many of the memories presented here. However, that’s exactly why you should read a book like this: to hear what happened, in all its unrefined glory.