Late last year, I went down into my basement, as one does, looking around for some forgotten something or other. I came across a few boxes I hadn’t opened in some time and, curious, popped them open to find what I guess I’d call the Basement Papers: spiral notebooks with interview transcriptions from the pre-computer days and other printouts from the Paleolithic computer era (anyone remember ATEX? I thought not). I began writing about rock ‘n’ roll in 1976 for a plethora of outlets, but mostly for the Boston Globe, 26 years through 2005. Parts of what follows originally appeared in a long-gone newsprint monthly magazine in Boston called Sweet Potato.

There were gay rockers in the 1970s, of course. But those were different times.

Everyone in Elton John’s inner circle knew—the public not so much, until the Rolling Stone reveal. Freddie Mercury, same deal, although the physical clues were hard to miss. David Bowie and Lou Reed certainly flirted with the imagery and appeared at least to be bisexual.

Judas Priest’s Rob Halford? Everything about the band’s lyrics, album cover art work and Halford’s appearance screamed GAY: a sailor’s cap with chains on it, leather pants, leather jacket, bare chest, studded wristband and toting a whip on stage. But the band denied it for years. I was talking to guitarist Glenn Tipton on the phone in 1988 and asked about it. (Yes, it was posed at the end of an interview.) He figuratively hit the roof, yelled at me for the temerity of asking, denied it and stopped the interview. Halford came out ten years later.

Tom Robinson, singer-bassist-main songwriter for the Tom Robinson Band, was something else entirely. He wrote “Glad to Be Gay,” on the 1978 EP Rising Free (in the UK) and it was included on their US debut LP Power in the Darkness. It was the first explicitly gay anthem on the punk/new wave radar. And, yes, it was radical back then.

Robinson approached the topic as a bittersweet celebration, something of both a dirge and a wry music hall singalong. It was about the apparent “acceptability” of homosexuality in Britain as it conflicted with the real-life consequences and prejudices (For what it’s worth, the three other guys in the band were straight, but politically on the same team).

While that is certainly the song the TRB is best remembered for, gay life/rights was just a sliver of their activist-oriented rock. And, it wasn’t all activism either. Their first UK hit, “2-4-6-8 Motorway,” was a Slade-like stomper, an out-and-out celebration of life behind the wheel, as much so as anything Bruce Springsteen had written. I only found out years later that the title came from a gay liberation chant of the day, “2-4-6-8/Gay is twice as good as straight.” Oh, and there’s a reference to the trucker in the song riding with “Lady Stardust,” which I later found out meant, as the Rolling Stones once put it, “cousin cocaine.”

You wouldn’t call the Tom Robinson Band a punk group per se—they were more Kinks-ian than Sex Pistols-ian—but they certainly rose out of that same agitated squall, benefiting from all the doors suddenly kicked open. In Britain, they were a Top 10 band and one of the prime movers behind that country’s Rock Against Racism movement.

They flickered briefly—by the end of 1979, they were done—but brightly. There were reunion gigs in 1987, 1989, and most recently in 2018. A UK tour celebrating the singer’s 70th birthday is happening in Spring of this year. It’s unclear how much of the original lineup will be present. Guitarist Danny Kustow, with whom Robinson often feuded, died last May of double pneumonia and a liver infection.

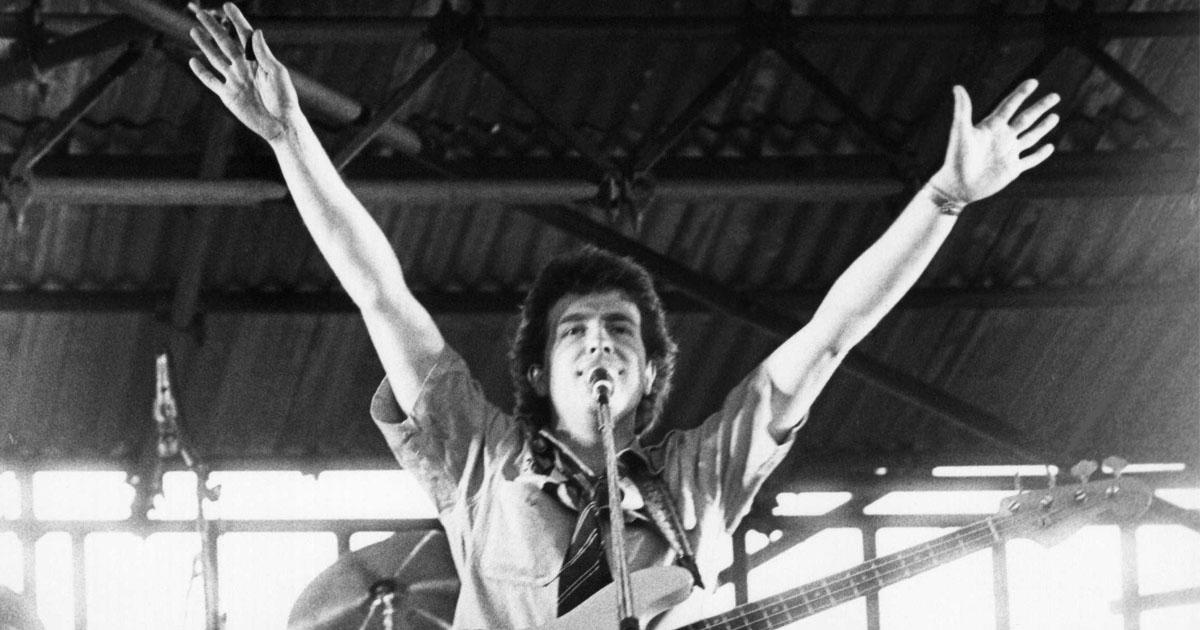

I saw the Tom Robinson Band at the soldout Paradise rock club in Boston in July 1979. It was a galvanizing gig and I remember having that feeling that of being in sync with so many there: those on stage, those surrounding me in the crowd. I wrote that the TRB put on a performance that equaled Graham Parker and Rumour in terms of intensity and red-hot passion. That was pretty much the standard-bearer of the time, Parker coming off the trifecta of albums, Howlin’ Wind, Heat Treatment and especially Squeezing Out Sparks, and putting on incendiary concerts.

On Robinson, I wrote, “he’s got ideas, and he’s got principles, but he’s no proselytizer. He’s as much a confident rocker as he is a perceptive songwriter. And it’s not so much you agree with everything Robinson says—he, in fact, doubts the true beliefs of some who ‘seem’ to agree—but that you form some kind of attitude and not get swept away in the apathetic tides of the day. Bluntly put, the Tom Robinson band makes it hard to go back to conventional (read: escapist) rock ‘n’ roll.”

The next day, I had an interview with Tom at an appropriate rock ‘n’ roll time, noon-ish, and at his choice of eatery, McDonald’s. Why? Tom wanted an Egg McMuffin. Alas, he was denied. In America, Mickey D’s didn’t serve that breakfast offering at lunch time. So, he bought a bunch of burger-y food and divvied it up among me, my photographer B.C. Kagan and Tom’s boyfriend at the time, Ned. The Sweet Potato headline for the story: BREAKFAST IN AMERICA: BURGERS, FRIES AND PIES WITH TOM ROBINSON. He was an engaging, glib conversationalist and “woke” compared to many of his contemporaries, almost four decades before the term existed.

Hard Noise: So, here on your first real US tour. How has the reaction been to “Glad to Be Gay”?

Tom Robinson: In terms of city to city and from crowd to crowd, some crowds are up for it, some crowds don’t know what to make of it, some crowds are embarrassed, some crowds get insecure.

That was a good bit you did last night, to stop the song in the middle and “apologize” if anybody got offended.

Yeah, I generally do that in places where I feel there will be some people thinking, “Y’know, fuck that.” But not saying anything.

We’re a pretty liberal city. You think a lot of people felt that way last night?

Yes. I don’t believe that that many people in a room would be unanimously in favor of “Glad to Be Gay” as appeared to be, in as far as the vaguely beatific smiles and people looking unfazed. I felt there was a lot of people stifling. I just don’t believe that [big a] percentage of a city could be pro-gay…but that song needs doing. You can’t let it get to the point where it ceases to be a challenge or else you just stop singing it. There’d be no point in singing the fucker if it just became cool, hip and institutionalized.

It could be a heavy thing—like, it’s not hip to been as a racist and it’s not hip to be anti-gay. So, you don’t show it when the song’s going. You just keep it to yourself.

In London at the Hammersmith Odeon, we played it there for the first time and everybody was singing [the refrain] so I stopped three again and I went over and kissed [keyboardist] Ian Parker on stage in the middle of the song. You could feel the shock wave to right through the audience like a big shudder. “Oooh!” Really, like it’s one thing to say, “Oh yeah, we support gays,” but to actually see two men kissing on stage in front of 2,000 people! And somebody I know was sitting near the back of the hall and two guys where behind him. When that happened, they’d been singing along and a soon as I kissed Ian, one said to the other, “You know something? I think these geezers are queer!”

Tom, you quote the Sex Pistols line “We mean it, man!,” Johnny Rotten’s sneer from “God Save the Queen” on the jacket of your second LP, TRB 2. Certainly, they broke a lot of ground for bands like yours, but at the same time they were hardly concerned with the ideals you espouse.

No, of course not. That’s the point of the quote. “We mean it, maaan!” was the most famous saying of 1977. That was definitely the catchphrase of the year. The hippie thing you know with “peace, love we mean it man” and when Rotten sneers “We mean it, maaan!” it’s like he does and he doesn’t.

How do you react to a song like the Pistols “Bodies,” a pretty vicious anti-abortion song?

Well, you’ve got to remember John Lydon was brought up as a Catholic and who knows what kind of play that may have had in his background in terms of the way it’s going to affect his lyrics. Have you heard that Graham Parker has one, too, “You Can’t Be Too Strong”?

I have. It’s a wrenching ballad. That seems to be more of a personal statement than a wide-ranging statement.

If you’ve had a girlfriend that’s had an abortion ’cause she’s not strong enough to take it and she didn’t actually want to have an abortion—she wanted to have the kid—than you’re going to get emotionally involved in the thing. Reviewers, I’ve noticed, alternately either hate it or love it.

You’re heavily involved with Rock Against Racism. A few years ago, Eric Clapton made some racist remarks during a concert. What was your take?

This is important really, actually, in light of the Elvis Costello thing. [In March 1979, Costello, drunk in a bar with Steven Stills and Bonnie Bramlett, called Ray Charles “a blind, ignorant nigger.” He later apologized.] Elvis is obnoxious and he never said he wasn’t. I can’t defend him on grounds of being a “nice, personable human being.” He’s been obnoxious to everybody, including me. But whatever Elvis Costello is, he’s not a racist. You’ve only got to listen to the lyrics of “Two Little Hitlers,” “Night Rally” and “Goon Squad” to find out what he thinks about racists.

You can’t really have a dual standard going for you. If Eric Clapton hadn’t existed, it would have been necessary to invent him. There was a need for Rock Against Racism, as witnessed by the fact that it took off so big when it happened. Eric Clapton’s chance drunken remarks were the spark for that, that lit the forest fire. But if it hadn’t been him, it would have been something else that would have provided, if you like, an excuse for the whole thing to get going.

So, in a way, we must be very grateful to Eric Clapton for those remarks at the right time; if Elvis had said that at that time it might have been Elvis instead. I don’t suppose Clapton meant it any more than Elvis; witness the fact that he’s taking Muddy Waters along with him [on tour] at the moment. At the same time, it seemed very shocking, Clapton saying that the flow of black people into Britain should be curbed because he didn’t want to live with too many of them, because Clapton made his name and his living and got substantially rich from playing black people’s music. People do get drunk; people do say daft things. I think his track record since then has shown that he can’t really be a substantial racist. Maybe he’s just too thick to work it out.

You’re a pop star and you’re an activist. Do you find any contradiction between the two?

I don’t care what categorization they put us in if they still listen to the band. Whatever you are, you can’t be a political activist if nobody listens to you and you can’t be a pop star if no one listens to you.

***

Robinson, who’s now 69, formed another short-lived band, Sector 27, after the TRB collapsed, suffered a nervous breakdown, went solo, had a UK hit (No. 6) with “War Baby” in 1983 and has continued making music. He’s also worked as a broadcaster with BBC 6.

Fifteen years after our breakfast in America, I talked to him on the phone for the Boston Globe. He finally had a US deal and a strong album, “Love Over Rage.” Moreover, he was a father and living with a woman, Susan Brearly, with whom he said he had “a full sexual relationship.” Yet, he still identified as gay.

In the song “Days,” Robinson sang, “And me, so glad that I’m a dad/And living with a girl/I hardly ever think about the days that changed the world.” In the next verse: “Sometimes in the dead of night, I dream of other men…”

So, I asked: Huh?

Robinson answered, “You sometimes meet another human being and you just really want to spend the rest of your life with them. You can’t imagine being without them and they enrich your life so utterly that you can’t worry if they’re the ‘wrong’ gender. I think the problem is people aren’t sure how to take it. They may think that the whole thing has been done for the sake of public effect, rather than the sake of private emotion. In terms of the public effect, I would have had a much easier life and a much smoother career path if I would have just continued singing ‘Glad to Be Gay’ on stage, then going quite secretly home and having my ‘shameful’ liaison with a woman as a guilty secret.”

He says that, yes, he got flack from the gay community, but said, “We’ve been fighting for tolerance for the last 20 years, and I’ve campaigned for people to be able to love whoever the hell they want. That’s what we’re talking about: tolerance and freedom and liberty—life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. So, if somebody won’t grant me the same tolerance I’ve been fighting for them, hey, they’ve got a problem, not me.”

“I am gay and I have never claimed to be anything else. I just happen to live with this woman that I get on with and that I’m happy to fancy. But I don’t go walking down the street and go, ‘Oh, look at that woman in the mini-skirt.’ I am gay. And I am in love with a woman. But the two are not incompatible. Deal with it.”

In a re-recorded version of “Glad To Be Gay,” on the 1996 album Having It Both Ways, he added a verse: “Well, if gay liberation means freedom for all, a label is no liberation at all.”