I once participated in one of those fatuous, yet irresistible, “best guitarists” polls and, not fatuously, nominated Gang of Four’s Andy Gill. Not most people’s first choice, and heresy to rock fans more enamored of the typical guitar hero type, Gill wasn’t Jimi Hendrix or Jimmy Page or Stevie Ray Vaughan or, god forbid, Steve Vai. He was not the guy who took the mind-bending solo and posed on a figurative pedestal awaiting big claps and a standing O.

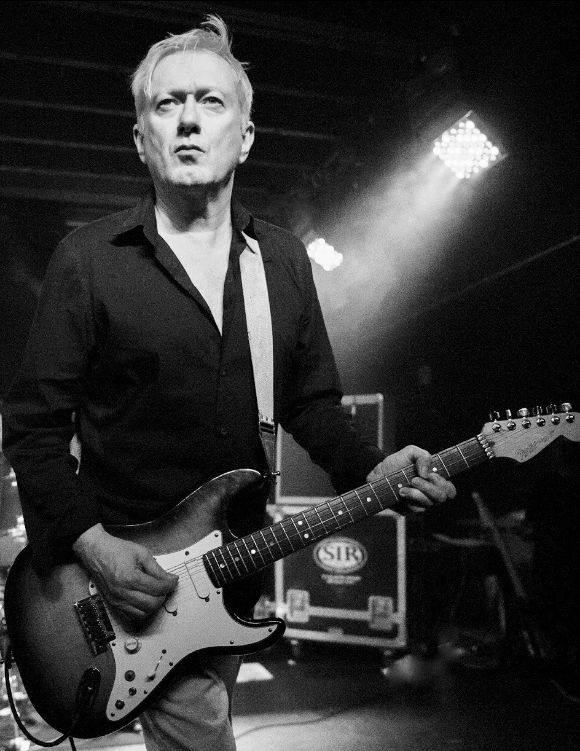

“Jagged” and “angular” were the two words most employed when describing Gill’s attack. And it was an attack. Short, staccato bursts that disrupted and detonated as much as drove the sound forward. Sharp shards of sound. Lightning bolts thrown across the stage. Seeing Gang of Four in 2015, 35 years after the first time, I was taken by Gill’s guitar work during “Not Great Men” all over again, it being like a downed electrical wire, sparking furiously along the pavement.

“People have a signature to their way of playing you can’t get away from,” Gill told me in 2011. “The surprise when we first emerged was great, but then, to a certain extent, people get familiarized with that shock. I think what I like is to reinvent [my sound] in different ways.”

Gill, who was 64, died on Feb. 1, in a London hospital’s intensive care unit. Following a tour late last year, he checked in with a respiratory illness. The cause of death was pneumonia.

Original drummer Hugo Burnham posted this on Facebook, speaking for himself, singer Jon King and bassist Dave Allen: “As the founder members of Gang of Four, some 40-odd years ago, we fondly remember the good times when the four of us wanted to change the world. Andy was our brother. We made a lot of great noise and art together. We had a few drinks. We traveled the world and made friends. We made people dance, and think, and laugh, and love. We laughed together. A lot. Our hearts go out to his wife, Catherine and his brother, Martin.”

Gill’s wife, Catherine Mayer, tweeted: “This pain is the price of extraordinary joy, almost three decades with the best man in the world.”

Shellac and Big Black guitarist (and Nirvana producer) Steve Albini tweeted, “From the first minute I played guitar I wanted to sound like Andy Gill. I never got there, but his minimal, jagged rhythmic sense left its fingerprint on everything I did.”

The Gang, formed in Leeds in 1976, came out of punk, but often played a sort of heady, mutant art-funk, influenced by the music of James Brown and the guitar work of Dr. Feelgood’s Wilko Johnson or P-Funk’s Eddie Hazel. As to Gill, his sound influenced Nirvana, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Fugazi, Bloc Party, Franz Ferdinand, Rage Against the Machine and countless others. Rage’s Tom Morello went appropriately gonzo on Instagram: Gill’s “jagged plague disco raptor attack industrial funk deconstructed guitar anti-hero sonics and fierce poetic radical intellect were formative for me.”

The ferocity—both physical and intellectual—of early Gang of Four was something to behold. Some of the songs, like “I Found That Essence Rare,” and “Damaged Goods,” had deep hooks, but establishing and repeating a melodic hook wasn’t what the group was aiming for. “There’s a lot more to music than the idea of a dominant line,” King told me in 1980, after an ecstatic gig at the Channel club in Boston. “African music is not based on melody; our music is based on grinding rhythms. We wanted to make something that was uniquely ours, that no one had done before. What I like about music is dancing. I don’t like singing along.”

Lyrically, they hurled all kinds of questions, conundrums and confrontations at you. “We do put forward anti-authoritarian ideas,” King said. “They’re not Marxist ideas, but they’re leftist ideas. I don’t know if the distinction is apparent in America, but there’s a whole left thing that does not have a Marxist basis to it.”

The Gang of Four used to strike some (sometimes, me) as grim and ultra-serious. King disagreed with that. “We are serious about what we do, but it’s a double-edged thing. It’s not bleak like Joy Division. I think humor is an essential part of it—not a belly laugh, but a sort of wit. Using words in a sharp way.”

Although songwriting credits were spread among all four members for their jaw-dropping “Entertainment!” debut album, the credits were mostly winnowed down to King and Gill over time. (Canadian writer Jim Dooley published an exhaustive book on the band, especially looking at those early years, in Red Set: A History of Gang of Four in 2017. Also check out Kevin Dettmar’s 2014 contribution to the 33 1/3 series, Entertainment!)

The Gang hit hard and topics ranged from the anti-chauvinistic “Guns Before Butter,” to the modern phenomenon of watching war on TV, “5.45” (“Guerilla war struggle is a new entertainment.”) In “We Live As We Dream, Alone” the band pretty much nailed the isolation many of us felt, even in a crowded room of rock fans.

Gill sang, but was never the Gang’s primary singer; that was the ever-kinetic King job. But Gill sang a few tunes and in “I Will Be a Good Boy,” which I saw them do at a 1982 concert, there was a line that pretty much summed up this band’s essence: “Dance to the tension of a world on the wane.”

Later came “Damaged Goods,” “Natural’s Not in It,” “Not Great Men” and “I Love a Man in a Uniform,” full-tilt frenzy. Gill’s asymmetrical guitar lines clanged and collided with Burnham’s beats and Sara Lee’s bass—a right jolly chaos. (Lee had replaced Dave Allen by that point; he’d left to form Shriekback.)

It’s well worth noting, too, that Gill had been involved on the production level for years, going back to the Chili Peppers and including the Stranglers, Michael Hutchence, Killing Joke, Therapy?, the Jesus Lizard and the Futureheards.

The Gang, still a living breathing, touring, recording entity right up until Gill’s death, had 11 players over the years, always anchored by Gill and, mostly, King. When Gang of Four showed up for an album, What Happens Next, and tour in 2015, King was not with them. Gill and King had what we might politely call “differences.”

The original Gang of Four hadn’t existed for many years, aside from a one-off re-recording of early material in 2004 and a 2005 reunion tour.

Bassist Thomas McNiece had been part of the Gang for eight years, drummer Jonny Finnegan was the new kid behind the kit, replacing Mark Heaney who’d been there since 2006. The guy at the mic was then-25-year-old Jon “Gaoler” Sterry. He met Gill when he went in the studio to work on a non-Gang related project. They clicked, King exited the group, and Gill wanted to carry on.

“When I started with the band, I was a fan, but I didn’t realize the legacy I was stepping into,” Sterry said, post-show, backstage. “I try to keep the energy Jon King was doing, but I’m trying to do my own thing, too.”

He admitted audiences greeted him with an attitude of “what have you got. Hopefully, we can win them over and toward the end of our shows it’s been positive.”

In 2011, Gill and I were talking about Content, their first disc in 16 years. “This time around,” said Gill, “I think there was an unspoken feeling, more than anything, to chip away anything that was less than essential, to discover what the essence is about. I think to a certain extent it’s not so much trying to sound like the first or second album, it’s asking very similar questions and coming up with answers that are not that dissimilar to the answers we came [to] back a while ago. You have to do it in a way that’s fresh, new and exciting. And that might mean defying convention in the way of going about it.”

“I think the thing is what I do on the guitar sounds like me,” Gill continued. “That’s something important. With this record, some of the tunes, I had melodies in my head and sequences and notes and things I thought were great. But when I played them the way they sounded sonically, it was ordinary. It wasn’t gonna work and I had to chip away at that. I said [to myself], ‘Do it like you’re Andy Gill.’ A penny dropped. ‘That’s what I’ll do.’”

Content was a strong album, one that did recall the early Gang in its attack and sound. “Riveting and robotic, they still have the capacity to thrill” wrote Mojo Magazine. “As bold and combustible as a clenched fist, Content is a remarkably good comeback,” wrote Artrocker. Importantly, it positioned the band as one not just trading on nostalgia, but still a viable, creative, working entity. It gave them currency and renewed cachet.

Gill concurred. “I often wonder why the hell didn’t we do this sooner. It’d be hard to explain, but it does occur to me. It’s enormously enjoyable going through the recording process, getting it done and out there. I think there’s an appetite for what it is we do. People want something which is a bit more—that questions some version of reality. I think there is a hunger for that.”

Who was out there attending the shows? Well, certainly people like me—around the same age as Gill—but also the kids who’ve picked up on what Go4 did, learned the language, and knew why they still mattered.

“One thing that happened in 2005 when we first did some gigs with Dave and Hugo,” said Gill, “is we didn’t know exactly what to expect. The audience was actually about 50 percent under 24. Young people!”

I have loved and continued to love Gill’s guitar sound—those spikes and shards, those seismic bursts that drove songs so that they imploded as much as exploded. The Gang of Four of 2015 and the one I saw again in early 2019 recreated something that was once ground-breaking: this politically charged, acerbic art-funk-punk that is now part of our common language.

When Gill and I spoke after the 2015 set at the Paradise, it was his first time through town without King fronting the band. “Over many decades, it’s been a stop-start operation with Jon,” he said. “Sometimes he’s enthusiastic and keen and sometimes he loses interest. In 2011, he said ‘That’s it, I’m done.’ He saw the project as limited. I said, ‘I’m going to carry on with the band.’ When people respond, I’ve found most people are happy with it, accept it. Is it really Gang of Four? Was it when Dave and Hugo left? I don’t care.”

As to owning the name, Gill said, “The basic point is I contributed the music—I’m the musical director—and some of the lyrics.” No one would argue Gill’s status as co-leader back in the heyday, but there was some dissent in the old Gang camp about some of those statements.

I looked at it this way: This is the Gang we’ve got, maybe the last Gang in town. I was sorry about the tattered history, the rumors of financial strife and frayed emotions. I wish Gill and King had been able to come to some amicable agreement to keep the machine up and running as it had been for the 2011 album Content and subsequent tour. Don’t we always wish for those things? For the band we loved when we’re young to stay with us through life’s journey. But change is the only constant, and I was glad that constant remained in my post-punk life, decades after my first jolt.

Now, that’s over and done.

Well, maybe. On Instagram the band wrote: “Our great friend and Supreme Leader has died today. Andy’s final tour in November was the only way he was ever really going to bow out, with a Stratocaster around his neck, screaming with feedback and deafening the front row. His uncompromising artistic vision and commitment to the cause meant that he was still listening to mixes for the upcoming record, whilst planning the next tour from his hospital bed…We’ll remember him for his kindness and generosity, his fearsome intelligence, bad jokes, mad stories and endless cups of Darjeeling tea. He just so happened to be a bit of a genius too. One of the best to ever do it, his influence on guitar music and the creative process was inspiring for us, as well as everyone who worked alongside him and listened to his music.”