Phuc Tran is the kind of teacher who makes anything interesting. The kind who gets over 100,000 people to watch his TEDx talk on Vietnamese grammar—for fun. The kind who tells you about his work as a sought-after tattoo artist until you start wondering about the next opening in his schedule.

But long before he taught Latin or opened a tattoo studio, Phuc Tran was a young refugee in a small American town, trying to make a life after escaping the violence of the Vietnam War. While often feeling estranged from both society at large and his own family, Phuc began finding truth and camaraderie in the seemingly opposed worlds of classic literature and punk rock.

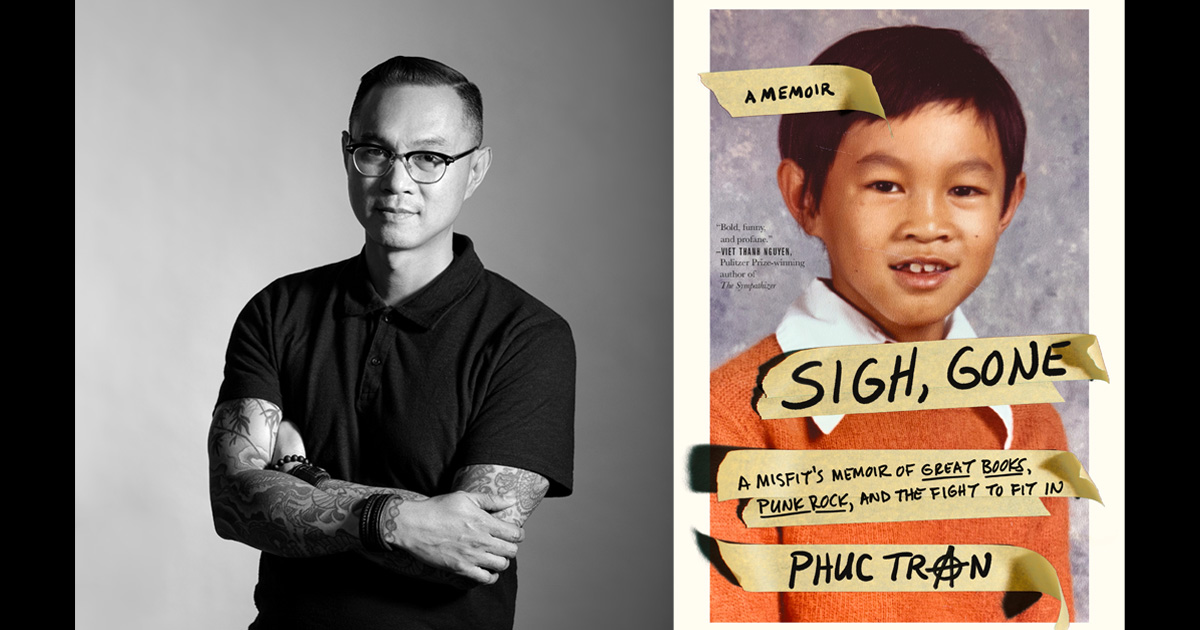

Phuc tells his story in Sigh, Gone: A Misfit’s Memoir of Great Books, Punk Rock, and the Fight to Fit In, which comes out today. So to celebrate the release of his new book and mark the 45th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, we talked to Phuc about his early brush with death, how he deals with prejudice, and why the best literature can be so punk.

HARD NOISE: How did you get from Vietnam to America?

PHUC TRAN: When it was clear that the South Vietnamese government was going to collapse, Gerald Ford signed this executive order called Operation Frequent Wind, which was basically, “We have to evacuate all South Vietnamese collaborators with the U.S. government. Otherwise, they will be summarily executed — like, they’re gonna get shot in a ditch.”

My family was part of that massive evacuation at the end of April 1975. We were going to get on a bus to an airfield to get out of there, and half of my family was on the bus. But I was just about two, and I was crying, freaking out, really throwing a temper tantrum. It got to the point where my grandmother was like, “Okay, let’s get off the bus and wait for the next one.” So we all got off the bus, and as it started pulling away, it was hit by mortar fire and blew up. Everybody on the bus died. So now I jokingly like to say, “My entire family owes me one.” We got on the next bus, and then went to the airfield.

The U.S. government had established four relocation camps for South Vietnamese nationals, and the one we went to was in Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania. It was a little bit like an animal rescue — we just kind of hung out there until American families would adopt us. These nice Lutherans from Carlisle, Pennsylvania showed up, and we got hooked up with this real estate developer, who helped my parents find a job, and he found us apartments. Then they would do monthly wellness checks, bringing us clothing and stuff. And they’d say, “Hey, have you figured out this whole Thanksgiving thing yet?” Or, “Here’s how Halloween works.” It was really pretty amazing.

HN: You also encountered some real racism and anti-immigration sentiment. Tell me a bit about what you experienced there.

PT: There was the classic schoolyard bullying, lots of racialized epithets, kids calling me “gook” or telling me to go back to my country. My family and I definitely experienced the clichés of anti-immigrant, anti-brown people rhetoric, and I’m not sure where it came from. I wish I had the opportunity to sit down with someone from that period and just be like, “Why did you tell me to go back to my country? Were you trying to have me feel fearful? Did you feel like I was getting too uppity?” I don’t want to shut down that conversation — I would really want to hear what they had to say.

Even now as a grown adult, I’m constantly having conversations with people about where I’m from, and whether I’m American or not. I took an Uber just the other day, and the guy was like, “Where are you from?” And I was like, “Pennsylvania.” And that turned into, “Where are you really from?” I said, “I was born in Saigon,” and he’s like, “Oh, you’re pretty much American.” I was like, “That’s so interesting — he feels like he can tell me that I get to belong.”

My wife was super pissed about it, but I try to hear the intent behind it. I can’t change the interaction, but I can look at it and be like, “You know what, he was trying to say a nice thing, trying to let me know that I do belong, and it just came out in a weird, goofy way.” I can let it ruin my day, or I can be like, “It made for a funny story. I’m gonna move on.”

HN: You came to love both punk music and literature. How did that happen?

PT: The discovery of punk rock was really just through skateboarding. I started skating with these kids, and I was like, “What are you guys listening to?” And they’re like, “Agent Orange.” It was so antithetical to whatever was on the radio at the time — Madonna, Phil Collins, super overproduced top-40 stuff. This was made by kids who were just two or three years older than me, and it was such a revelation. I remember hearing swears, hearing them saying “fuck” or whatever, and I was like, “Whoa, you can say that?” That broke open a whole bunch of barriers for me — like, what can music do? What can art do?

As for the book thing, a friend of mine just lent me a book, Albert Camus’ The Stranger. I read it and I was like, “Huh, that was really intense, and kinda weird.” When I mentioned it in school, my teachers and my classmates were like, “Whoa, you read?” And I realized that if I read books, people will think I’m smart. So I didn’t start reading because I loved books — I started reading because it gave me some social cachet. And I ended up loving it.

HN: At first, punk and literature seem like very different things. And yet in the book, you point out that there are some writers and intellectuals who are very punk rock. I couldn’t help but think of that Rage Against the Machine song “Renegades of Funk,” which talks about Chief Sitting Bull, Thomas Paine, MLK, and Malcolm X being renegades. What is so punk rock about some of these thinkers?

PT: I think Thoreau is a great example. Thoreau wrote Civil Disobedience where he was like, “I’m not gonna pay taxes — I’d rather go to jail!” And then he’s like, “Fuck everybody, I hate everyone. I’m gonna go live in a cabin!” (Never mind that the cabin wasn’t actually that far out of town) So I think the spirit of punk has been picked up by people who are willing to be nonconformists.

Especially if there’s injustice — those intellectual renegades you’re talking about were speaking to things that they saw as unjust. For me, that was the most interesting side of punk rock. Like the Sex Pistols — when they came out, their whole thing was, “We hate everything.” They literally said that. But then when Joe Strummer and Mick Jones were trying to put together The Clash, they were like, “Well, I don’t know if we hate everything.” Because if you hate everything, you just want to blow everything up — that’s the nihilism of that early ’70s punk.

But I think The Clash were more thoughtful, and they were really about social injustices. They were talking about things like racial profiling by the English police, stagnant wages for the working class, and affordable housing. The Clash were politically so far ahead of their time. And I’ve always gravitated toward that, that punk is just another vehicle to talk about injustices. Or at least name them, try to reckon with them, and create a dialogue around them, much in the way that Thoreau, Emerson, and other seismic writers were trying to do.

HN: In your book, you write, “Punk rock was an explosive for detonating the present so that I could rebuild my future from the rubble.” So maybe that nihilistic tendency toward destruction is still useful, provided that it’s part of a larger arc of building something better.

Thinking about punk rock, literature, and even your personal journey, I feel like all three of these things are exercises in trying to make yourself heard or understood, just in different ways. For punk rock, it’s by screaming into a microphone. For literature, it’s by writing about a problem you’re wrestling with. And for your personal journey, you’ve chronicled it in your book. It makes me wonder — is everything we do just an attempt to make ourselves heard and understood?

PT: Yeah, you named two of the three things that I think are so critical for us as human beings: You want to be seen, you want to be understood, and you want to be valued. So it’s like, “I see you, I hear what you’re saying, I think you’re saying something important, and I want you to feel good about it.” It seems so small when you distill it like that, and yet you can go your whole life and never find it.

You need the larger community to be part of that experience, but the tricky thing is that punk is like, “I don’t need anybody! I’m an island!” And that’s romantic, but I think you do need some validation from the community. We’re social creatures — we need each other. So we live in this constant tension of, “I want to be an individual, but I also need to feel loved by the community. But I’m also an individual, so don’t steamroll me with your external values!”

That external validation is important — it’s part of the social contract. It’s choosing to celebrate other people, and you want to feel that that’s reciprocated for you, too.

HN: Maybe that’s why Thoreau didn’t go so far away after all.

PT: Yeah, it’s funny, right? He goes off to this shack where he’s like, “Fuck everybody! I’m gonna write this book! . . . Hey, you guys wanna read my book?”

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

photos: Jeff Roberts Imaging