A favorite pastime of cinephiles is imagining movies that almost were. Speculation on what could have been is often fueled by pre-production artifacts, like the concept art from Alejandro Jodorowsky’s abandoned Dune adaptation, or the leaked polaroid of Nic Cage’s costume test for Tim Burton’s scrapped Superman Lives. But sometimes, all we’re left with is the music. Here are five albums that were originally intended to accompany movies that never happened.

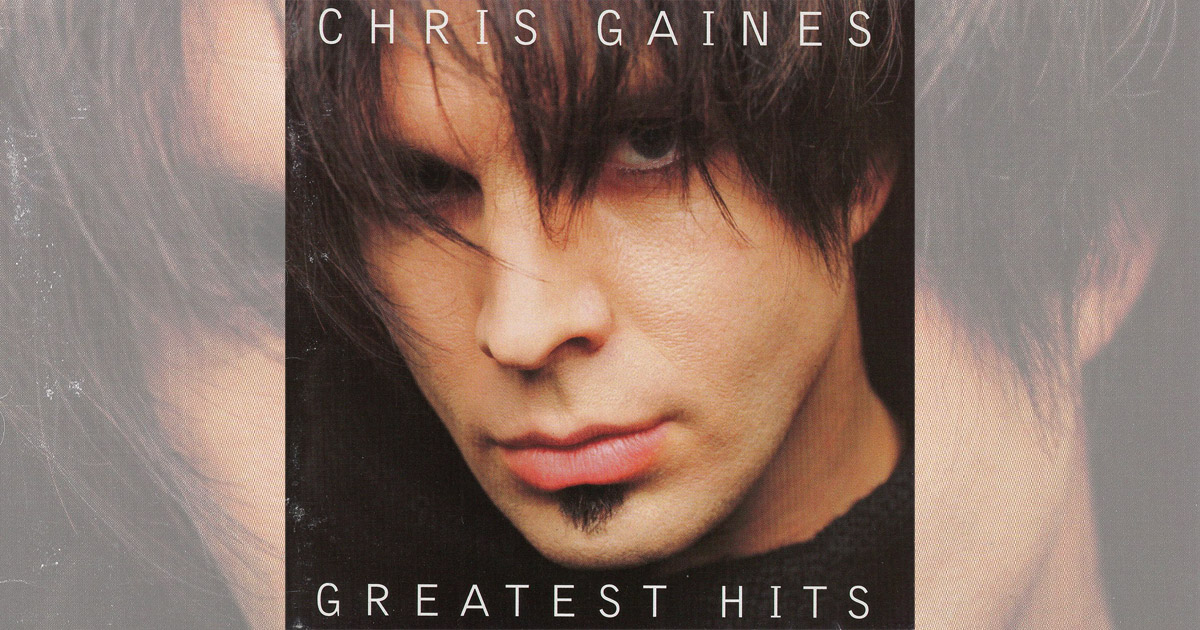

Garth Brooks in… The Life of Chris Gaines (1999)

Garth Brooks was left holding the bag for his failed alter-ego experiment, Chris Gaines, but it was producer Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds who had the idea for a movie about a music superstar whose untimely death spurs a fan to investigate foul play. Brooks would portray Gaines on record, only appearing in the film through interview and archival footage. Die Hard screenwriter Jeb Stuart had already been secured to write the thriller, tentatively titled The Lamb. But as Brooks began recording music for the project, he took it upon himself to flesh out Gaines’ detailed backstory, spanning five chart-topping albums and plagued by plane crashes and sex addiction.

Brooks refused to write any music for the album because he didn’t want the character tainted by his own musical influence, so nearly every Gaines song came from the back catalogue of Gordon Kennedy, Wayne Kilpatrick, and Tommy Sims, the songwriting team behind Eric Clapton and Babyface’s very VH1 hit, “Change the World.” For authenticity, Brooks built each track around the original years-old demo, including some recorded in Kennedy’s garage. However, none of the resulting music reflected the excess portrayed in the Chris Gaines VH1 Behind the Music episode that aired; it’s difficult to imagine the adult contemporary soft rock of “Lost in You” appearing on an album called Fornucopia.

The Life of Chris Gaines was unveiled to the public before The Lamb was even in production, a strategy that was supposed to generate buzz but ultimately left audiences puzzled. The movie halted completely during the prolonged illness of screenwriter Stuart’s wife, but in 2019, Brooks cryptically told The Tennessean, “The Gaines project isn’t done.”

Neil Young – After the Gold Rush (1970)

Many people know actor Dean Stockwell as Al, the cigar-chomping hologram from Quantum Leap, or as Ben, the mysterious, bleary-eyed pimp in Blue Velvet. But another generation knew him as a child actor in countless MGM productions, or as the co-star of 1959’s Compulsion, alongside Orson Welles. What happened between these two careers can most accurately be summarized as, “the ’60s.” Stockwell dropped out of the entertainment industry and became a fixture of the Topanga Canyon art scene in Los Angeles. A picture taken by Stockwell of experimental filmmaker Wallace Berman appeared on The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album cover.

Hoping to take advantage of Dennis Hopper’s development deal following Easy Rider, Stockwell wrote a screenplay titled After the Gold Rush, that he described as “a Jungian discovery of the Gnosis.” No known copies of the script exist, but according to scattered accounts, the story climaxes with a giant tidal wave wiping out Topanga. Canyon resident and fellow former child actor Russ Tamblyn was set to play an aging rock star living in a castle, and Stockwell asked Tamblyn’s neighbor, Neil Young, to write the soundtrack.

Released six months after CSNY’s immaculately sterile Deja Vu, After the Gold Rush was the first of many Neil Young albums recorded in a home studio with all live vocals. Although the back cover states that “most” of the album was inspired by Stockwell’s screenplay, Young only recalls writing two songs specifically for the project: “Cripple Creek Ferry,” and the cosmic, French horn-laden title track. The song “After the Gold Rush” was written to score a scene in which assemblage artist George Herms carries the Tree of Life through Topanga Canyon to the ocean.

Universal was reportedly moving forward with the movie until Stockwell spooked studio execs by giving them a tour of his world, introducing them to proposed cast members like Janis Joplin. Young and Stockwell later collaborated on another movie idea that never got off the ground called The Tree From Outer Space, and one that actually did get made: the slapstick nuclear comedy Human Highway, featuring a band that Stockwell had turned Young onto called Devo.

My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult (1987)

Franke Nardiello was a photography student in Chicago when he helped Marston Daley get settled after a move. They both worked for the influential punk and new wave record label Wax Trax!, a driving force behind the burgeoning industrial scene. The pair never really hit it off when they met on tour with Ministry, (Nardiello did lights and Daley played keyboards) but as neighbors, they discovered a mutual affection for foreign horror and B movies rented from the store around the corner. The two conceived of an art film titled Hammerhead Housewife and the Thrill Kill Kult, based on a tabloid headline Nardiello had seen years earlier while living in London. Their vision for the movie drew inspiration from filmmaker Russ Meyer, director of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, and the Roger Ebert-penned Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. When asked in 2012 about the appeal of Russ Meyer, Nardiello answered, “Boobs. I just like them.”

Not surprisingly, Hammerhead Housewife’s soundtrack began to take shape before anything else, and after Wax Trax! Expressed interest in releasing the music, the project was abandoned and the movie became the band. Nardiello and Daley took on the stage names Groovie Mann and Buzz McCoy, and My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult’s self-titled EP was released in 1987.

The Thrill Kill Kult movie may have been scrapped, but the group appeared onstage during the famous nightclub scene in The Crow and wrote original music for Paul Verhoeven’s misunderstood epic Showgirls. You can even hear their surprisingly loungey Smash Mouth precursor, “Hit & Run Holiday,” on The Flintstones soundtrack.

The Kinks – Arthur (Or the Decline and Fall of the British Empire) (1969)

After hearing the character-driven concept album The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, producer Jo Durden-Smith approached Ray Davies to commission a pop opera for Granada Television. Davies developed a story based on his new collection of songs with writer Julian Mitchell, later known for the play and movie Another Country. The movie would be a day in the life of Arthur Morgan, a war veteran and carpet layer whose family and country move on without him as he begins to shed his conditioning and see that trading his whole life for a modest house and car may have been a bad deal. Morgan was inspired by Arthur Anning, the man who married Davies’ sister Rose and fled a changing Britain by emigrating to Australia, a continent portrayed in song on Arthur as a worry-free Utopia.

With the album recorded and the script finalized, Frank Finlay of Lifeforce fame was cast in the lead role and shooting was set to begin. However, the studio pulled the plug during a meeting where the producer failed to provide detailed budgetary information. In the album’s liner notes, Mitchell mentions the Granada TV special as though it was still forthcoming, but it never happened, a loss made all the more disappointing because Davies had so much to say about class, war, and nationalism that remains painfully relevant today. But in 2019, Davies and the BBC brought Arthur to life as a radio play to celebrate the album’s 50th anniversary. Meanwhile, we’re still waiting for Bobcat Goldthwaite’s Schoolboys in Disgrace movie.

Kiss – Music from “The Elder” (1981)

In 1981, Kiss were looking to get back into the good graces of loyal fans alienated by the pop sound of Unmasked. The band set about recording a set of straight ahead rock songs, until producer Bob Ezrin read a short story/screenplay by bassist Gene Simmons. “The Elder” is an epic tale of good and evil conceived by Simmons at the Beverly Hills Hotel, and Ezrin, having just had a high-concept risk pay off with Pink Floyd’s The Wall, was convinced this was the direction the next Kiss album needed to go.

Perhaps more than a little inspired by the recent success of the Star Wars franchise, the story centers on a chosen one, referred to as “The Boy,” who must overcome his fear under the training of an old mentor named Morpheus. For the album, actors were hired to portray the characters in narrative transitional passages, including Chris Makepeace from Meatballs. The album also features members of the American Symphony Orchestra, the St. Roberts Choir, and a songwriting assist from Lou Reed, who helped give voice to the story’s demonic villain, “Mr. Blackwell.”

As the story ends, The Boy has found his courage and is ready to do battle, and… that’s it. This was intended as the first of many Elder projects that would include sequel albums and a major motion picture. But Casablanca Records did away with almost all of the album’s dialogue and further jumbled the narrative by rearranging the tracklist to highlight the singles. Music from “The Elder” was released to confused fans wondering why Kiss weren’t on the cover. The album disappeared from the charts almost immediately, and whatever movie deal Simmons was working on went with it. For the first time ever, Kiss didn’t support their album with a tour, instead opting for a few promotional TV appearances like the sketch comedy show, Fridays.

Bob Ezrin has since blamed his clouded judgement during the project on — you guessed it — cocaine, and Paul Stanley described the album as simultaneously ambitious and lazy in his memoir Backstage Pass, saying, “It would have been more of a challenge to make a hard rock album. That would have taken a lot of effort.”

The world never got an Elder movie, but eighteen years later, The Matrix introduced the world to a new chosen one, helped to realize his abilities by a mentor named Morpheus. Coincidence?