My adolescent too-cool-for-school attitude took away opportunities from me. I wish I was talking about actual school — no, I was pretty good at that. Actually, the thing I’m referring to was less about education and more of a religion, one led by nine masked figures clad in jumpsuits numbered 0 through 8.

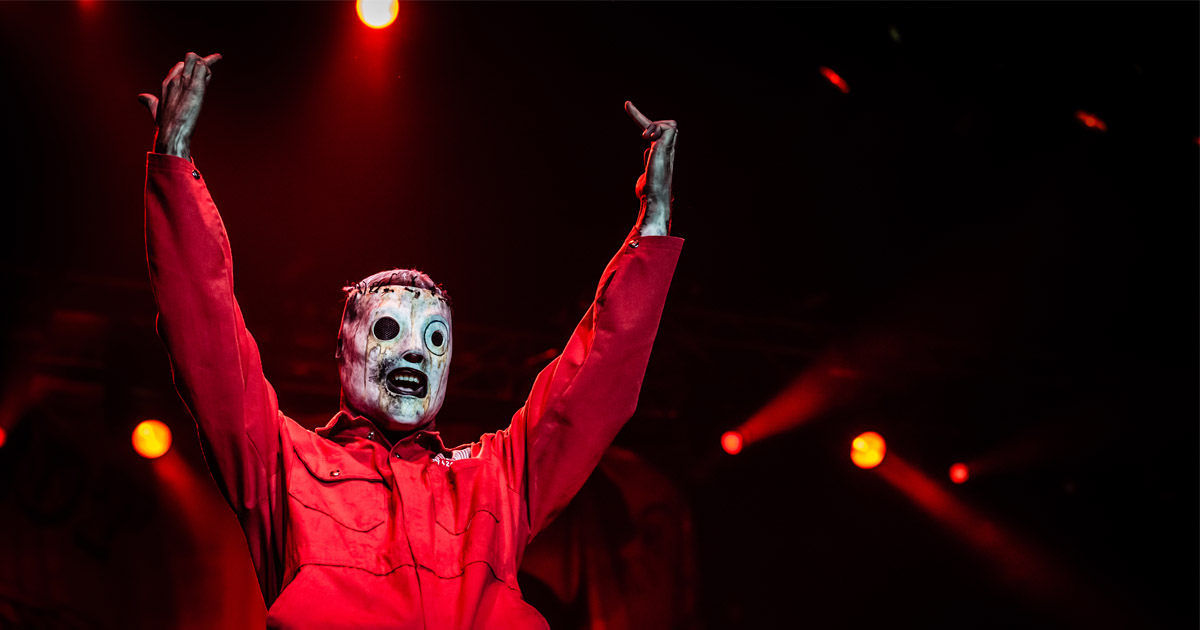

Slipknot’s masks changed in varying degrees with each album cycle. While a mask with a dick nose might elicit laughs, Mick Thomson made old-school hockey goaltender protection look more threatening than Jason Voorhees, while Corey Taylor’s visage delivered various deranged characters. It was an easy way to attract younger fans, appearing larger than life and far from human.

But while other young metalheads became enamored with the facades, I viewed it as a marketing ploy. The band’s chance with me ended there. Hit Parader magazine, essentially an extension of the Nine’s press team given regular cover appearances, was nicknamed “Shit Parader” and the mere mention of Iowa — a place I had no prospects of visiting — was met with a scoff. That says a lot about the band’s success, though. Slipknot became synonymous with their Midwestern home to the point where they were the only reference to the state for many.

For a band so over-the-top, it’s the subtleties that made them. Cheeky quips about their trash can players were common, but the added percussionists were used to add weight to beats, rather than crafting their own rhythms. Their sparsity would make room for visual chaos in the band’s live shows. Hell, even the decision to start numbering the members at #0 feels masterful in hindsight. On one hand, it underlines their lyrics’ nihilistic point of view, but it also allows each listener to feel they round out the ranks as number 10, while receiving the all-important #9 as their title.

These details demand attention that could get lost in the noise — both audio AND visual. Truthfully, I can’t remember how much of their music I had even heard at the time, aside from the singles. That didn’t help their case, seeing as Corey’s croon flexed melodic muscle hard and often. The beefiest of those songs came in the unavoidable “Before I Forget” from Vol. 3: (The Subliminal Verses) — and Guitar Hero 3: Legends of Rock. The song’s presence in the video game du jour hammered its hook into heads, as hands tried to lock down the seemingly unattainable perfect playthrough.

It was similarly polarizing to some fans, too, who lamented the decrease in brutality. Indeed for outsiders it could be difficult to view Slipknot as a bonafide metal band without understanding their mastery of hooks complements their brawn instead of superseding it.

The release of 2008’s All Hope Is Gone was a big deal for Maggots, coming a whole four years after their previous LP. That no doubt felt like an eternity at the time, though is shorter than any wait since (hindsight is both 2020 and a jerk). It was also the turning point for my appreciation of the band. “Psychosocial” felt heavier than most singles, which hooked me, but it was the death metal influences on the title track and “Sulfur” that had me line and sinker. Perhaps the claims I’d read of Slipknot being the closest death metal had gotten to the pop charts weren’t so far fetched after all.

I then took my first trip to Iowa, a purposeful one not just passing through, and was blown away by the brutal blasts that opened “People = Shit.” Hell, the choral repetition of the title maintained the spirit by screaming instead of reaching for melody. When they did attempt that, as on “My Plague,” it kept an upbeat energy that was as undeniable as the crunchy groove that surrounded it. “The Heretic Anthem” and its brutal proclamation of “If you’re 555, then I’m 666” became a mantra for maggots. But “Disasterpiece” contains the album’s most aggressive lyric: “I want to slit your throat and fuck the wound.”

Sold as I was on much of the band’s sophomore release, its self-titled pre-cursor and subtler follow-up didn’t click with me until a 2016 interview with Taylor revealed he considered Slipknot the bridge between nu metal and the New Wave of American Heavy Metal.

Listening back, the raw delivery on “Wait and Bleed” felt more like a cry for help than a demand for radio play. Everything about the 1999 self-titled felt authentic in a way that the maligned subgenre hadn’t achieved since Korn’s 1994 debut. In many ways, the albums served as bookends on the sound’s validity as artistic expression, whereas Limp Bizkit’s bro aesthetic would exploit it for edginess’ sake and Linkin Park masterfully used it as a launching pad for radio rock.

If Iowa was the pre-cursor to bands like Killswitch Engage and As I Lay Dying, Vol. 3 was their first as peers. The higher pitched runs on hits like “The Blister Exists” and “Opium of the People” were Slipknot’s riffier elements (think melo death influencing the NWOAHM), while the focus on choruses mirrored metalcore’s most mainstream tenets. If I may, b-side “Scream” is one of the best songs from this session, with bouncy riffs colliding with a meaty and energetic chorus.

All three albums of the opening trilogy maintained their own identity, while remaining distinctly Slipknot. Their fourth album found them smartly and smoothly reaching out of their bubble. The aforementioned death metal influence came about as deathcore was breaking — Suicide Silence joined Slipknot on that year’s Mayhem Festival — and the hammer-ons and pull-offs on opener “Gematria (The Killing Name)” felt closer to the New Wave (of American Heavy Metal) than the nu wave.

I could talk about my feelings about .5: The Gray Chapter or We Are Not Your Kind, but those can be read or watched in my reviews. Instead, I’ll let this grin on my face communicate the distance I traveled in my journey to appreciate Slipknot.