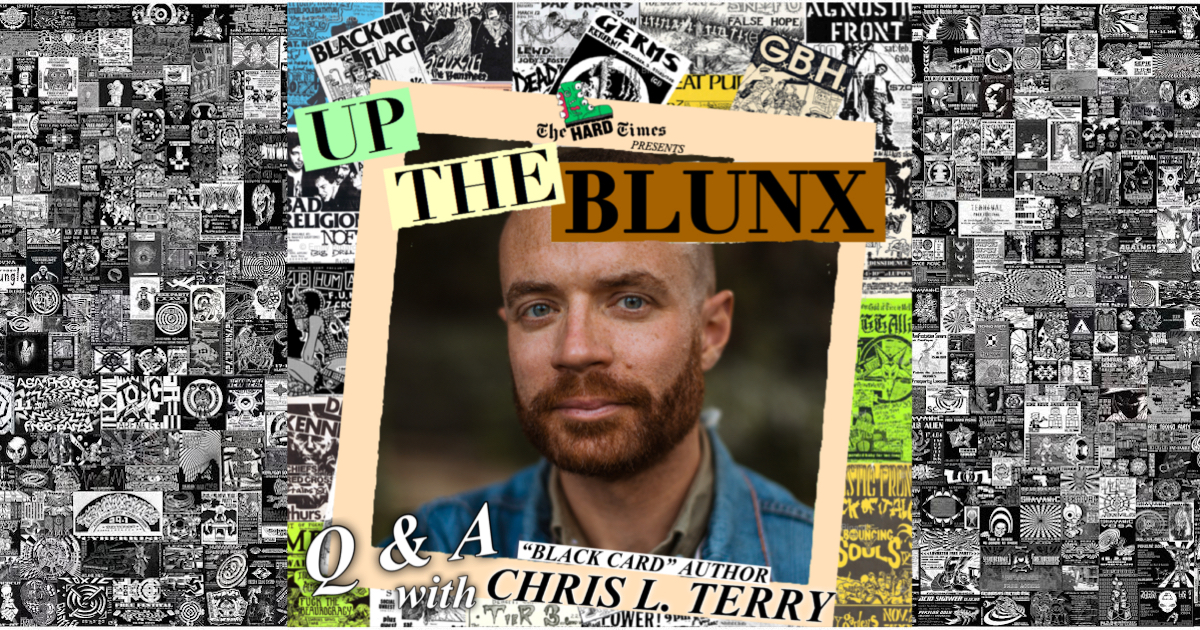

Up the Blunx is a podcast where two Black punks from different walks of life get together to voice their opinions on everything from straight edge to condiments to the police. The show, from comedian Kevin Tit and End It frontman Akil Godsey, regularly features music from Black artists. In this series, we dig a little deeper into the artists featured on Up the Blunx. This week’s Q&A is with the author of Black Card, Chris L. Terry, who was featured on episode 14.

Would you walk us through your process for how you developed the story for Black Card?

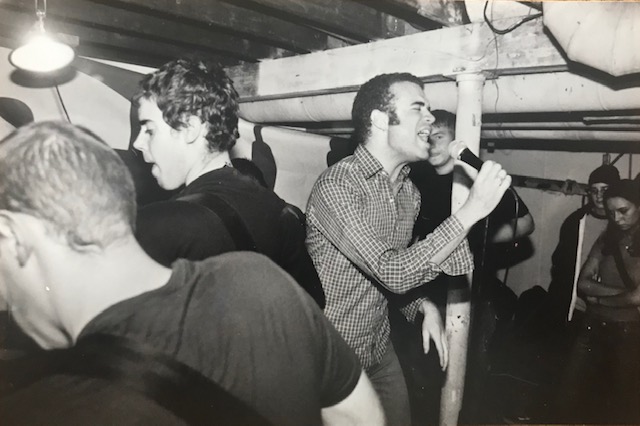

Black Card is a fictional novel inspired by my experiences in the Richmond, Virginia punk scene in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It’s about a mixed-race punk bassist with a black imaginary friend, who takes away his Black Card — his credibility as a black person — when he stays quiet during a racist incident. While trying to win back his Card, the nameless narrator is accused of a violent crime, which makes him reconsider his ideas about blackness and the way that the world sees him. It’s set in early ‘00s Richmond, so there’s plenty of sweaty house shows, dusty cafes and good old fashioned racism.

I started by just writing down memories: inside jokes, weird details of Richmond life, and moments where I felt like my blackness and my punkness were in opposition.

I looked for recurring details and incidents to base the story and characters on and shuffled it around into a narrative, adding in some supernatural shit as a way to put the identity stuff into action.

I was a new parent with a 9-5 job, so it was slow going. I’d set small goals like, “write 500 words a day.” I managed a draft a year for three years before it felt done enough to try to get it published. The book dropped in August 2019 and was one of NPR’s best books of the year. Now I have to write another one. Crap.

What was it about punk that you gravitated towards?

My family was having money problems and I felt like, if you could play the game and still fall on your face, then what was the point of trying? The American Dream is bullshit! I loved how punk celebrated underdogs, and DIY was about making a small world for yourself. That egalitarian, “anyone can do it” ethos was really attractive at a time when I was feeling like I wasn’t “enough” anything — black enough, white enough, rich enough. I could be punk enough.

Looking back, I know that I also got so into punk because it was a way to avoid my complicated racial identity. It’s easier to be like, “Dude, I’m punk!” than to say, “Well, I’m black, but my mom’s white, and I have blue eyes, but my hair’s nappy…”

That was 1995 and I was sixteen, living in Richmond, Virginia. Our apartment was near the college (and also by the huge Robert E. Lee Confederate monument), and I started going to shows with some guys I skated with. There were a variety of exciting, genre-bending punk bands in Richmond then: (Young) Pioneers, Inquisition, Action Patrol, Hose.Got.Cable., Maximilian Colby, Damn Near Red, Four Walls Falling, and Eucharist, for starters.

I always liked guitar music. My father, my black parent, is a guitarist and music lover, and I grew up hearing Prince, Hendrix, Muddy Waters and Thin Lizzy at home. My mixtapes in high school were like Assfactor 4/Wu-Tang/one of Dad’s Curtis Mayfield 45s… I still listen to all that.

Do you remember any specific time while playing in bands where you felt a sort of identity crisis?

Do I ever! I remember…

…worrying that people wouldn’t be able to tell I was into hardcore because I couldn’t have swoopy emo bangs like the white boys…

…when everyone went back to the ‘burbs after all-ages shows in the city…

…when kids I met’s parents didn’t want them coming over because where I lived was “dangerous” (read: black)…

…when I was connecting to Outkast and Mos Def at home and I had no clue how to make my art reflect that…

…when a black friend from high school came to my first punk house and just stood in the middle of the kitchen, looking rightfully grossed out…

…and, of course, the overt racism: when white punks “ironically” played white power records, when their hesher friend said Jimi Hendrix was “pretty good at guitar…for a black guy,” and that horrible year or two when Confederate flags were trendy in Richmond’s punk/metal scene. Never mind the times I overheard anti-black racist shit and just felt so invisible.

What are some things you see in punk now that you wish were around when you were younger? What are some things about those earlier years that you wish were still around?

Punk seems way more diverse now, in terms of race, gender, sexuality, everything. I love it. The first time I heard Soul Glo, I was pissed off like, “Where was this twenty years ago when I needed it?”

There’s also more conversation around privilege right now and I think that has chilled out some of the dogma around DIY politics without watering down the values. Making music and touring is expensive and difficult, and therefore a privilege. As the scene diversifies, there are more people who don’t have as much of a safety net as the average straight/cis white boy. Part of making punk inclusive is finding ways to level the playing field so that people who don’t have their parents’ credit cards can also have a voice. That seems to be happening.

What do I wish was still around from the ‘90s? The Offspring! Just kidding. I do wish I could see some bands again, but that’s just for my own nostalgia purposes. I don’t think that punk has lost anything important in the last twenty-five years. I might actually like it more now than I did then, if I could only stay up past 10pm to enjoy it.

If you could give some words of encouragement to a younger version of yourself what would they be?

Punk and blackness are not mutually exclusive. Don’t diminish your blackness to fit into punk.

If you’re black, in a punk band, and would like your music featured on the show, send a bio and link to your music to [email protected]